Poetry - Burns Night

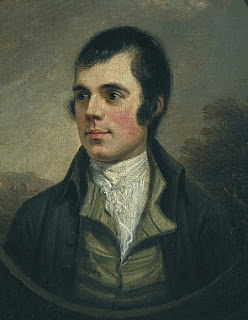

For Robert Burns' birthday, a reminder of our own sleekit, cow'rin Susan Omand's look at the traditional celebrations of Burns Night ...

Happy Burns Night. And, yes, please note it’s not Burns DAY, it has to be a night; otherwise we don’t get the traditional Burns Supper event, which is probably the closest a lot of Scots, and others who celebrate it, get to poetry readings at any time of the year. Burns Suppers have been on the go a long time, with the first being held by friends and associates of Robert Burns in 1801, five years after his death, who gathered to eat, drink and be merry and remember the myriad of work of their friend who died at the relatively early age of 37 after complications from dental problems. However, in his short life he managed to write many hundreds of poems on a huge variety of subjects and father twelve children, the last of whom was born on the day of his funeral.

His most famous poems, of course, romanticise love (Ae Fond Kiss or My Luve is Like a Red Red Rose for example) and the rural idyll of the farming community Burns worked in, as that is the wishful remembrance of ex-pat Scots. To A Mouse is one such farming poem, written on breaking a mouse’s nest while ploughing, and contains the very famous line “The best-laid schemes o' mice an 'men Gang aft agley." that gave John Steinbeck the title to his novel Of Mice and Men. However, a much larger portion of his work had strong political overtones, a disdain for religion and a knack of bitingly sardonic, but very funny, social commentary. To a Louse is a great example of the latter as he sat in church watching a louse crawl through the hair of the very snobby woman sitting in the pew in front. This is the poem that also gives us the line “O wad some Power the giftie gie us to see oursels as ithers see us!” There are also many far more ribald than romantic poems in his portfolio if you care to go looking for the Merry Muses of Caledonia (may I suggest Ken ye na Oor Lass Bess? or Nae Hair On't as examples – although his poem entitled Cock Up Your Beaver is not nearly as crude as it sounds and is actually about a feather in a soldier’s hat) and I’m sure that these would never grace a Burns Supper event. You can find a full linked list of his poetry, thanks to the BBC website here.

The tradition of the Burns Supper has continued every year since 1801 and spread, with 25th January, Burns’ birthday, becoming recognised as an unofficial National Day in Scotland, with Burns Suppers, of haggis, neeps (turnips if you're Scottish, Swede if you're English) and tatties (potatoes) and much whisky, being held on or around that date in many formal and less formal establishments, from family gatherings to large banquets. Whatever the size of event though, the format of a Supper is always the same and, although most of the poetry and speeches can be chosen to suit, there are a few that must be said or sung. So let me take you through a typical running order for how we celebrate Scotland’s favourite bard:

At formal gatherings, it is traditional for the top table guests to be piped in and the assembled crowd clap along to welcome them. The top table is usually made up of those who are going to speak or entertain throughout the evening as well as any other “important” guests. There is always a Master of Ceremonies for the evening who welcomes the guests, introduces the top table and any other speakers and entertainers before reciting the Selkirk Grace, the only semi-religious content of the evening, giving thanks for the meal about to be eaten:

‘Some hae meat and canna eat, and some would eat that want it, But we hae meat, and we can eat, Sae let the Lord be thankit’.

Everyone has to stand up as the haggis is piped in and taken to the top table. Traditionally the chef carries the haggis in on a silver platter behind the piper and they are followed by the person who will address the haggis.

The person addressing the haggis gives an often overly-dramatic recital of Burns’ poem To a Haggis with much wielding of a very sharp knife. On a given line in the poem (“His knife see Rustic-labour dight”), the speaker slices the haggis along its length, making sure to spill out some of the insides* (“trenching its gushing entrails”). The recital ends with the platter being raised above their head whilst saying the triumphant words ‘Gie her a Haggis!’ to rapturous applause. Everyone, including the chef and the piper, then raises their glasses for a toast and shouts 'The Haggis' before it is piped back out to be served up.

The meal is eaten before the rest of the entertainment ensues. Once everyone has finished eating and the drinking is well underway, the first entertainment is introduced and a Burns poem or song performed. Then comes The Immortal Memory, where the main speaker for the evening gives his view of Burns’ life and works, including his poetry, politics, national pride, faults and humour in a speech that should be as entertaining as the man himself was without ridiculing him. The speaker always ends with a heart-felt toast: 'To the Immortal Memory of Robert Burns’.

There’s another chance for a Burns song or poem to be performed before the traditional Toast to the Lassies is given, always by a man. This is a humorous speech written for the evening containing quotes from Burns work that poke fun at the shortcomings of women but is still funny for the whole audience. Despite the teasing, the speech always ends on a positive note with the speaker asking the men to raise their glasses in a toast 'to the lassies'.

After another song or poem is performed, the Lassies get their revenge with a Reply to the Toast. A female speaker begins with a sarcastic thanks on behalf of the women present for the previous speaker's 'kind' words, before giving a spirited speech highlighting the failings of the male of the species, again using reference to Burns and the women in his life.

After a final song or poem from “the entertainment” the Master of Ceremonies offers a Vote of Thanks and the supper ends, as does everything these days, with a heartfelt rendition of Burns’ most famous song, Auld Lang Syne. A quick side note for all of you folk who have been doing the hand-crossing thing WRONG for all these years, you don’t cross hands with your neighbour until you sing the line 'And there's a hand my trusty fiere' which is half way through the song. Oh, and at no point is it ever “for the sake of” anything. Do it right or don’t do it at all! [Susan rants more - oh so much more - about this every New Year over on AlbieMedia here - Ed.]

So now you can join in with the traditional Burns Night celebrations of Scotland’s National Bard and look as if you know what’s going on, even if you don’t understand a word of what’s said at the time. Just don’t ever admit at one of these things that you don’t like haggis!

*No haggises were harmed in the writing of this article.

Images - Wikipedia

The tradition of the Burns Supper has continued every year since 1801 and spread, with 25th January, Burns’ birthday, becoming recognised as an unofficial National Day in Scotland, with Burns Suppers, of haggis, neeps (turnips if you're Scottish, Swede if you're English) and tatties (potatoes) and much whisky, being held on or around that date in many formal and less formal establishments, from family gatherings to large banquets. Whatever the size of event though, the format of a Supper is always the same and, although most of the poetry and speeches can be chosen to suit, there are a few that must be said or sung. So let me take you through a typical running order for how we celebrate Scotland’s favourite bard:

At formal gatherings, it is traditional for the top table guests to be piped in and the assembled crowd clap along to welcome them. The top table is usually made up of those who are going to speak or entertain throughout the evening as well as any other “important” guests. There is always a Master of Ceremonies for the evening who welcomes the guests, introduces the top table and any other speakers and entertainers before reciting the Selkirk Grace, the only semi-religious content of the evening, giving thanks for the meal about to be eaten:

‘Some hae meat and canna eat, and some would eat that want it, But we hae meat, and we can eat, Sae let the Lord be thankit’.

Everyone has to stand up as the haggis is piped in and taken to the top table. Traditionally the chef carries the haggis in on a silver platter behind the piper and they are followed by the person who will address the haggis.

The person addressing the haggis gives an often overly-dramatic recital of Burns’ poem To a Haggis with much wielding of a very sharp knife. On a given line in the poem (“His knife see Rustic-labour dight”), the speaker slices the haggis along its length, making sure to spill out some of the insides* (“trenching its gushing entrails”). The recital ends with the platter being raised above their head whilst saying the triumphant words ‘Gie her a Haggis!’ to rapturous applause. Everyone, including the chef and the piper, then raises their glasses for a toast and shouts 'The Haggis' before it is piped back out to be served up.

The meal is eaten before the rest of the entertainment ensues. Once everyone has finished eating and the drinking is well underway, the first entertainment is introduced and a Burns poem or song performed. Then comes The Immortal Memory, where the main speaker for the evening gives his view of Burns’ life and works, including his poetry, politics, national pride, faults and humour in a speech that should be as entertaining as the man himself was without ridiculing him. The speaker always ends with a heart-felt toast: 'To the Immortal Memory of Robert Burns’.

There’s another chance for a Burns song or poem to be performed before the traditional Toast to the Lassies is given, always by a man. This is a humorous speech written for the evening containing quotes from Burns work that poke fun at the shortcomings of women but is still funny for the whole audience. Despite the teasing, the speech always ends on a positive note with the speaker asking the men to raise their glasses in a toast 'to the lassies'.

After another song or poem is performed, the Lassies get their revenge with a Reply to the Toast. A female speaker begins with a sarcastic thanks on behalf of the women present for the previous speaker's 'kind' words, before giving a spirited speech highlighting the failings of the male of the species, again using reference to Burns and the women in his life.

After a final song or poem from “the entertainment” the Master of Ceremonies offers a Vote of Thanks and the supper ends, as does everything these days, with a heartfelt rendition of Burns’ most famous song, Auld Lang Syne. A quick side note for all of you folk who have been doing the hand-crossing thing WRONG for all these years, you don’t cross hands with your neighbour until you sing the line 'And there's a hand my trusty fiere' which is half way through the song. Oh, and at no point is it ever “for the sake of” anything. Do it right or don’t do it at all! [Susan rants more - oh so much more - about this every New Year over on AlbieMedia here - Ed.]

So now you can join in with the traditional Burns Night celebrations of Scotland’s National Bard and look as if you know what’s going on, even if you don’t understand a word of what’s said at the time. Just don’t ever admit at one of these things that you don’t like haggis!

*No haggises were harmed in the writing of this article.

Images - Wikipedia

Post a Comment